Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article is about the cemetery in Concord, Massachusetts. For the cemetery of the same name in New York, see Sleepy Hollow Cemetery . Family plot of the Thoreaus in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. The grave of Louisa May Alcott at Sleepy Hollow. The grave of Franklin Benjamin Sanborn at Sleepy Hollow. Sleepy Hollow Cemetery is a cemetery located on Bedford Street near the center of Concord, Massachusetts. The cemetery is the burial site of a number of famous Concordians, including some of the United States' greatest authors and thinkers, especially on a hill known as "Author's Ridge."

- // [edit] History Sleepy Hollow was designed in 1855 by noted landscape architects Cleveland and Copeland, and has been in use ever since. It was dedicated on September 29, 1855; Ralph Waldo Emerson gave a dedication speech and would be buried there decades later.[1] Both designers of the cemetery had decades-long friendships with many leaders of the Transcendentalism movement, and their design reflects that.

- The Alcott family, including Amos Bronson Alcott (Transcendentalist, philosopher, educator), Abby May (Wife of Amos Bronson Alcott), and their daughter Louisa May Alcott (author of Little Women and others)

- Ephraim Wales Bull (inventor of the Concord Grape)

- William Ellery Channing (Transcendentalist and poet)

- Ralph Waldo Emerson (Transcendentalist and poet)

- Daniel Chester French (sculptor of the Lincoln Memorial)

- Nathaniel Hawthorne (author of The Scarlet Letter and others)

- Sophia Hawthorne (wife of Nathaniel Hawthorne)

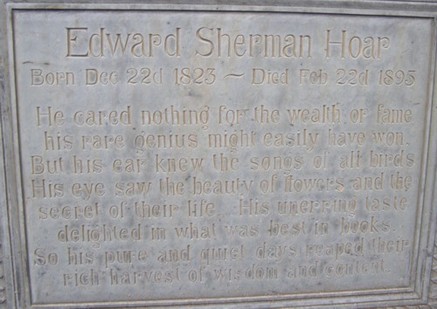

- George Frisbie Hoar (19th-century politician)

- Richard Marius (Reformation historian and Southern novelist)

- Ralph Munroe (yacht designer and pioneer of South Florida)

- Elizabeth Peabody (education reformer)

- Franklin Benjamin Sanborn (author and social reformer)

- Henry David Thoreau (Transcendentalist, philosopher, and author)

- George Washington Wright (California's first representative in Congress)

"Sleepy Hollow was an early natural garden designed in keeping with Emerson's aesthetic principles," writes Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn in his Nature and Ideology. In 1855, landscape designer Robert Morris Copeland delivered an address he entitled The Usefull [sic] and The Beautiful, tying his principles of naturalistic, organic garden design to Emerson's Transcendentalist principles. Shortly, afterward, Copeland and his partner were retained by the Concord Cemetery Committee, of which Emerson was an active member, to design a cemetery for the growing community.

On September 29, 1855, Emerson delivered the opening address of the cemetery's consecration.[2] In it he lauded the designers' work. "The garden of the living," said Emerson, was as much for the benefit for the living, to communicate their relationship to the natural world, as it was to honor the dead. By situating the monuments to the dead within a natural landscape, the architects conveyed their message, said Emerson. A cemetery could not "jealously guard a few atoms under immense marbles, selfishly and impossibly sequestering [them] from the vast circulations of nature [which] recompenses for new life [each decomposing] particle."[3]

Known as Sleepy Hollow for some 20 years prior to its use as a cemetery, the newly-consecrated landscape would, Emerson told his audience that September day in Concord, "When these acorns, that are falling at our feet, are oaks overshadowing our children in a remote century, this mute green bank will be full of history: the good, the wise, and the great will have left their names and virtues on the trees... will have made the air tuneable and articulate."

To realize their vision, Emerson noted that the cemetery's designers had fitted the walks and drives into the site's natural amphitheater. They also left much of the original natural vegetation in place, instead of removing it and replanting with ornamental shrubs, as was often the case. Several years after Emerson's address, a visitor to the new cemetery noted the abundance of wild plants such as woodbine, raspberry, and goldenrod, as well as the natural moss and roots of pine trees which were left in situ by the designers.[4]

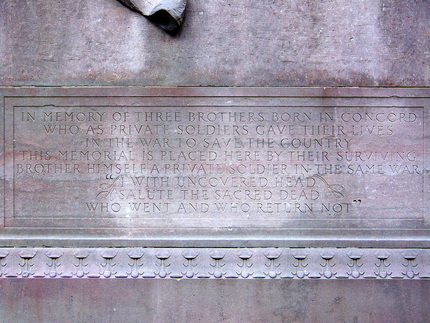

The Melvin Memorial, also known as Mourning Victory, sculpted by Daniel Chester French marks the grave of three brothers killed in the Civil War.

People are still being buried there. The back of the newer portion of the cemetery leads to a path system which connects to the Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge.

[edit] Notable burials Ralph Waldo Emerson's grave in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

|

Mourning Victory from the Melvin Memorial, 1906–8; this carving, 1912–15

Daniel Chester French (American, 1850–1931) Marble 120 1/2 x 57 1/4 x 28 3/4 in. (306.1 x 145.4 x 73 cm) Gift of James C. Melvin, 1915 (15.75) As early as 1897, Daniel Chester French was at work on a commission from James C. Melvin, a Boston businessman, to design a war monument honoring his three brothers who had died in the Civil War. In 1908, the Melvin Memorial was erected in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, Massachusetts, and is considered by many to be French's greatest war monument, if not his finest ideal work. Four years later, Melvin offered to fund a marble replica for the Metropolitan Museum, which was subsequently carved by the Piccirilli Brothers and installed in the Museum in 1915. French merged innovative technique and symbolic content in Mourning Victory, as he called the figure of the angel. She emerges from a cavity of a rectangular marble shaft, flesh from stone, darkness into light. The partial nude strides forward with hair and drapery swirling around her. The tip of a wing is visible near her knee. In one outstretched hand she holds a branch of laurel, while in the other she lifts above her head an American flag, its stars decisively rendered. This charged physical movement maintains a carefully orchestrated emotional balance with the melancholy restraint of the angel's downcast eyes. The Museum's version relates more closely to French's original model, because in the final design for the Melvin Memorial the figure was reversed. Apparently, the approach to the outdoor monument brought Mourning Victory's upraised arm in front of her face, nearly hiding it from that vantage point. Source: Daniel Chester French: Mourning Victory from the Melvin Memorial (15.75) | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art 19. Henry David Thoreau

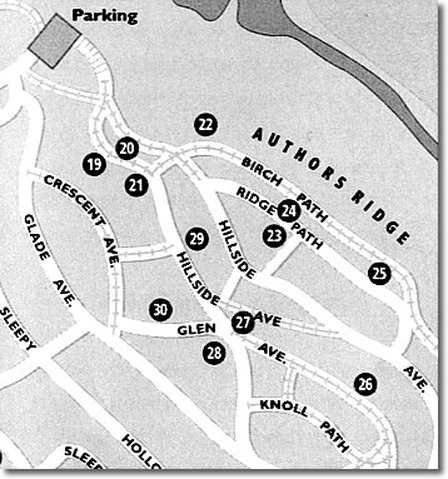

20. Nathaniel & Sophia Hawthorne 21. Alcott Family 23. Ralph Waldo Emerson & Family 24. Harriet M Lothrop ("Margaret Sidney") |